On one of the worst days of last year, to wit the first day of the Eton and Harrow match, I had turned into the Hamman1, in Jermyn Street, as the best available asylum for wet boots that might no longer enter any club. Mine had been removed by a little pinchbeck oriental2 in the outer courts, and I wandered within unpleasantly conscious of a hole in one sock, to find myself by no means the only obvious refugee from the rain. The bath was in fact inconveniently crowded. But at length I found a divan to suit me in an upstairs alcove. I had the choice indeed of more than one; but in spite of my antecedents I am fastidious about my cooling companions in a Turkish bath, and it was by no accident that I hung my clothes opposite to a newer morning coat and a pair of trousers more decisively creased than my own.

But the coincidence in pickle was no less remarkable. In ensuing stages of physical devastation one had dim glimpses of a not unfamiliar, reddish countenance; but with the increment of years it has been my lot to contract short sight as well as incipient obesity, and in the hot rooms my glasses3 lose their grip upon my nose. So it was not until I lay swathed upon my divan that I recognised E.M. Garland in the fine fresh-faced owner of the nice clothes opposite mine. A tawny moustache rather spoilt him as Phoebus, and there was a hint of old gold about the shaven jaw and chin; but I never saw better looks of the unintellectual order; and the amber eye was as clear as ever, the great strong wicket-keeper’s hand unexpectedly hearty, when recognition dawned on Teddy in his turn.

He spoke of Raffles without hesitation or reserve, and of me and my Raffles writings as though there was nothing reprehensible in one or the other, displaying indeed a flattering knowledge of those pious memorials.

“But of course I take them with a grain of salt,” said Teddy Garland; “you don’t make me believe you were either of you such desperate dogs as all that. I can’t see you climbing ropes or squirming through scullery windows—even for the fun of the thing!” he added with somewhat tardy tact.

It is certainly rather hard to credit now. I felt that after all there was something to be said for being too fat at forty, and that Teddy Garland had said it excellently.

“Now,” he continued, “if only you would give us the row between Raffles and Dan Levy, I mean the whole battle royal that A.J. fought and won for me and my poor father, that would be something like! The world would see the sort of chap he really was.”

“I am afraid it would have to see the sort of chaps we all were just then,” said I, as I still think with exemplary delicacy; but Teddy lay silent and florid for some time. These athletes have their vanity. But this one rose superior to his.

“Manders,” said he, leaving his divan and coming and sitting on the edge of mine, “you have my free leave to give me and mine away to the four winds, if you will tell the truth about that duel, and what Raffles did for the lot of us!”

“Perhaps he did more than you ever knew.”

“Put it all in.”

“It was a longer duel than you think. He once called it a guerilla duel.”

“Then make a book of it.”

“But I’ve written my last word about the old boy.”

“Then by George I’ve a good mind to write it myself!”

This was an awful threat. Happily he lacked the materials, and so I told him. “I haven’t got them all myself,” I added, only to be politely but openly disbelieved. “I don’t know where you were,” said I, “all that first day of the match, when it rained.”

Garland was beginning to smile when the surprise of my statement got home and changed his face.

“Do you mean to say A.J. never told you?” he cried, still incredulously.

“No; he wouldn’t give you away.”

“Not even to you—his pal?”

“No. I was naturally curious on the point. But he refused to tell me.”

“What a chap!” murmured Teddy, with a tender enthusiasm that made me love him. “What a friend for a fellow! Well, Manders, if you don’t write all this I certainly shall. So I may as well tell you where I was.”

“I must say it would interest me to know.”

My companion resumed his smile where he had left it off. “I wonder if you would ever guess?” he speculated, looking down into my face.

“I don’t suppose I should.”

“No more do I; not in a month of Sundays; for I spent that day on the very sofa I was on a minute ago!”

I looked at the striped divan opposite. I looked at Teddy Garland sitting on mine. His smile was a little wry with the remnant of his bygone shame; he hurried on before I could find a word.

“You remember that drug I had? Somnol I think it was. That was a risky game to play with any head but one’s own; still A. J. was right in thinking I should have been worse without any sleep at all. I should,” said Teddy, “but I should have rolled up at Lord’s! The beastly stuff put me asleep all right, but it didn’t keep me asleep long enough! I was awake before four, heard you both talking in the next room, remembered everything in a flash! But for that flash I should have dropped off again in a minute; but if you remember all I had to remember, Manders, you won’t wonder that I lay madly awake all the rest of the night. My head was rotten with sleep, but my heart was in such hell as I couldn’t describe to you if I tried.”

“I’ve been there,” said I, briefly.

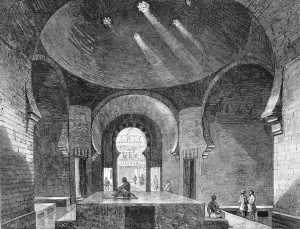

“Well, then, you can imagine my frightful thoughts. Suicide was one; but to get out of that came first, to get away without looking either of you in the face in broad daylight. So I shammed sleep when Raffles looked in, and when you both went out I dressed in five minutes and slunk out too. I had no idea where I was going. I don’t remember what brought me down into this street. It may have been my debt to Dan Levy. All I remember is finding myself opposite this place, my head splitting, and the sudden idea that a bath might freshen me up and couldn’t make me worse. I remembered A.J. telling me he had once taken six wickets after one. So in I came. I had my bath, and some tea and toast in the hot-rooms; we were all to have a late breakfast together, if you recollect. I felt I should be in plenty of time for that and Lord’s—if only I hadn’t boiled all the cricket out of me. So I came up here and lay down there. But what I hadn’t boiled out was that beastly drug. It got back on me like a boomerang. I closed my eyes for a minute—and it was well on in the afternoon when I awoke!”

Here Teddy interrupted himself to order whiskies and soda of a metropolitan Bashi-Bazouk4 who happened to pass along the gallery; and to go stumbling over to his pockets, in his swaddling towels, for cigarettes and matches. And the rest of his discourse was less coherent.

“Then I did feel it was a toss-up between my razor and a charge of shot5! I had no idea it was raining; if you look up at that coloured skylight, you can’t say if it’s raining now. There’s another sort of hatchway on top of it. Then you hear that fountain tinkling all the time; you don’t hear any rain, do you?—It was after three, but I lay till nearly four simply cursing my luck; there was no hurry then. At last I wondered what the papers had to say about me—who was playing in my place, who’d won the toss and all the rest of it. So I had the nerve to send out for one, and what should I see? ‘No play at Lord’s’—and sudden illness of my poor old father! You know the rest, Manders, because in less than twenty minutes after that we met.”

“And I remember thinking how fit you looked,” said I. “It was the bath, of course, and the sleep on top of it. But I wonder they let you sleep so long.”

“How could they know what I’d been up to?” said Teddy. “I mightn’t have had any sleep for a week; it was their business to let me be. But to think of the rain coming on and saving me—for even Raffles couldn’t have done it without the rain. That was the great slice of luck—while I was lying right there! And that’s why I like to lie there still—for luck rather than remembrance!”

The drinks came; we smoked and sipped. I regretted to find that Teddy was no longer faithful to the only old cigarette. But his loyalty to Raffles won my heart as he had never won it in his youth.

“Give us away to your heart’s content,” said he; “but give the dear old devil his due at last.”

“But who exactly do you mean by ‘us’?”

“My father not so much, perhaps, because he’s dead and gone; but self and wife as much as ever you like.”

“Are you sure Mrs. Garland won’t mind?”

“Mind! It was for her he did it all; didn’t you know that?”

I didn’t know Teddy knew it, and I began to think him a finer fellow than I had supposed.

“Am I to say all I know about that too?” I asked.

“Rather! Camilla and I will both be delighted—so long as you change our names—for we both loved him!” said Teddy Garland.

I wonder if they both forgive me for taking him entirely at his word?