1Raffles was still stamping and staggering with his knuckles in his eyes, and I heard him saying, “The letter, Bunny, the letter!” in a way that made me realise all at once that he had been saying nothing else since the moment of the foul assault. It was too late now and must have been from the first; a few filmy scraps of blackened paper, stirring on the hearth, were all that remained of the letter by which Levy had set such store, for which Raffles had risked so much.

“He’s burnt it,” said I. “He was too quick for me.”

“And he’s nearly burnt my eyes out,” returned Raffles, rubbing them again. “He was too quick for us both.”

“Not altogether,” said I, grimly. “I believe I’ve cracked his skull and finished him off!”

Raffles rubbed and rubbed until his bloodshot eyes were blinking out of a blood-stained face into that of the fallen man. He found and felt the pulse in a wrist like a ship’s cable.

“No, Bunny, there’s some life in him yet! Run out and see if there are any lights in the other part of the house.”

When I came back Raffles was listening at the door leading into the long glass passage.

“Not a light!” said I.

“Nor a sound,” he whispered. “We’re in better luck than we might have been; even his revolver didn’t go off.” Raffles extracted it from under the prostrate body. “It might just as easily have gone off and shot him, or one of us.” And he put the pistol in his own pocket.

“But have I killed him, Raffles?”

“Not yet, Bunny.”

“But do you think he’s going to die?”

I was overcome by reaction now; my knees knocked together, my teeth chattered in my head; nor could I look any longer upon the great body sprawling prone, or the insensate head twisted sideways on the parquet floor.

“He’s all right,” said Raffles, when he had knelt and felt and listened again. I whimpered a pious but inconsistent ejaculation. Raffles sat back on his heels, and meditatively wiped a smear of his own blood from the polished floor. “You’d better leave him to me,” he said, looking and getting up with sudden decision.

“But what am I to do?”

“Go down to the boathouse and wait in the boat.”

“Where is the boathouse?”

“You can’t miss it if you follow the lawn down to the water’s edge. There’s a door on this side; if it isn’t open, force it with this.”

And he passed me his pocket jimmy as naturally as another would have handed over a bunch of keys.

“And what then?”

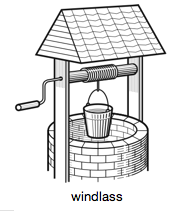

“You’ll find yourself on the top step leading down to the water; stand tight, and lash out all round until you find a windlass2. Wind that windlass as gingerly as though it were a watch with a weak heart; you will be raising a kind of portcullis at the other end of the boathouse, but if you’re heard doing it at dead of night we may have to run or swim for it. Raise the thing just high enough to let us under in the boat, and then lie low on board till I come.”

Reluctant to leave that ghastly form upon the floor, but now stricken helpless in its presence, I was softer wax than ever in the hands of Raffles, and soon found myself alone in the dew upon an errand in which I neither saw nor sought for any point. Enough that Raffles had given me something to do for our salvation; what part he had assigned to himself, what he was about indoors already, and the nature of his ultimate design, were questions quite beyond me for the moment. I did not worry about them. Had I killed my man? That was the one thing that mattered to me, and I frankly doubt whether even it mattered at the time so supremely as it seemed to have mattered now. Away from the corpus delicti, my horror was already less of the deed than of the consequences, and I had quite a level view of those. What I had done was barely even manslaughter at the worst. But at the best the man was not dead. Raffles was bringing him to life again. Alive or dead, I could trust him to Raffles, and go about my own part of the business, as indeed I did in a kind of torpor of the normal sensibilities.

Not much do I remember of that dreamy interval, until the dream became the nightmare that was still in store. The river ran like a broad road under the stars, with hardly a glimmer and not a floating thing upon it. The boathouse stood at the foot of a file of poplars, and I only found it by stooping low and getting everything over my own height against the stars. The door was not locked; but the darkness within was such that I could not see my own hand as it wound the windlass inch by inch. Between the slow ticking of the cogs I listened jealously for foreign sounds, and heard at length a gentle dripping across the breadth of the boathouse; that was the last of the “portcullis,” as Raffles called it, rising out of the river; indeed, I could now see the difference in the stretch of stream underneath, for the open end of the boathouse was much less dark than mine; and when the faint band of reflected starlight had broadened as I thought enough, I ceased winding and groped my way down the steps into the boat.

But inaction at such a crisis was an intolerable state, and the last thing I wanted was time to think. With nothing more to do I must needs wonder what I was doing in the boat, and then what Raffles could want with the boat if it was true that Levy was not seriously hurt. I could see the strategic value of my position if we had been robbing the house, but Raffles was not out for robbery this time; and I did not believe he would suddenly change his mind. Could it be that he had never been quite confident of the recovery of Levy, but had sent me to prepare this means of escape from the scene of a tragedy? I cannot have been long in the boat, for my thwart3 was still rocking under me, when this suspicion shot me ashore in a cold sweat. In my haste I went into the river up to one knee, and ran across the lawn with that boot squelching. Raffles came out of the lighted room to meet me, and as he stood like Levy against the electric glare, the first thing I noticed was that he was wearing an overcoat that did not belong to him, and that the pockets of this overcoat were bulging grotesquely. But it was the last thing I remembered in the horror that was to come.

Levy was lying where I had left him, only straighter, and with a cushion under his head, as though he were not merely dead, but laid out in his clothes where he had fallen.

“I was just coming for you, Bunny,” whispered Raffles before I could find my voice. “I want you to take hold of his boots.”

“His boots!” I gasped, taking Raffles by the sleeve instead. “What on earth for?”

“To carry him down to the boat!”

“But is he—is he still—”

“Alive?” Raffles was smiling as though I amused him mightily. “Rather, Bunny! Too full of life to be left, I can tell you; but it’ll be daylight if we stop for explanations now. Are you going to lend a hand, or am I to drag him through the dew myself?”

I lent every fibre, and Raffles raised the lifeless trunk, I suppose by the armpits, and led the way backward into the night, after switching off the lights within. But the first stage of our revolting journey was a very short one. We deposited our poor burden as charily as possible on the gravel, and I watched over it for some of the longest minutes of my life, while Raffles shut and fastened all the windows, left the room as Levy himself might have left it, and finally found his way out by one of the doors. And all the while not a movement or a sound came from the senseless clay at my feet; but once, when I bent over him, the smell of whiskey was curiously vital and reassuring.

We started off again, Raffles with every muscle on the strain, I with every nerve; this time we staggered across the lawn without a rest, but at the boathouse we put him down in the dew, until I took off my coat and we got him lying on that while we debated about the boathouse, its darkness, and its steps. The combination beat us on a moment’s consideration; and again I was the one to stay, and watch, and listen to my own heart beating; and then to the water bubbling at the prow and dripping from the blades as Raffles sculled4 round to the edge of the lawn.

I need dwell no more upon the difficulty and the horror of getting that inanimate mass on board; both were bad enough, but candour compels me to admit that the difficulty dwarfed all else until at last we overcame it. How near we were to swamping our craft, and making sure of our victim by drowning, I still shudder to remember; but I think it must have prevented me from shuddering over more remote possibilities at the time. It was a time, if ever there was one, to trust in Raffles and keep one’s powder dry5; and to that extent I may say I played the game. But it was his game, not mine, and its very object was unknown to me. Never, in fact, had I followed my inveterate leader quite so implicitly, so blindly, or with such reckless excitement. And yet, if the worst did happen and our mute passenger was never to open his eyes again, it seemed to me that we were well on the road to turn manslaughter into murder in the eyes of any British jury: the road that might easily lead to destruction at the hangman’s hands.

But a more immediate menace seemed only to have awaited the actual moment of embarkation, when, as we were pushing off, the rhythmical plash and swish of a paddle fell suddenly upon our ears, and we clutched the bank while a canoe shot down-stream within a length of us. Luckily the night was as dark as ever, and all we saw of the paddler was a white shirt fluttering as it passed. But there lay Levy with his heavy head between my shins in the stern-sheets6, with his waistcoat open, and his white shirt catching what light there was as greedily as the other; and his white face as conspicuous to my guilty mind as though we had rubbed it with phosphorus. Nor was I the only one to lay this last peril to heart. Raffles sat silent for several minutes on his thwart; and when he did dip his sculls it was to muffle his strokes so that even I could scarcely hear them, and to keep peering behind him down the Stygian7 stream.

So long had we been getting under way that nothing surprised me more than the extreme brevity of our actual voyage. Not many houses and gardens had slipped behind us on the Middlesex shore, when we turned into an inlet running under the very windows of a house so near the river itself that even I might have thrown a stone from any one of them into Surrey. The inlet was empty and ill-smelling; there was a crazy landing-stage, and the many windows overlooking us had the black gloss of empty darkness within. Seen by starlight with a troubled eye, the house had one salient feature in the shape of a square tower, which stood out from the facade fronting the river, and rose to nearly twice the height of the main roof. But this curious excrescence only added to the forbidding character of as gloomy a mansion as one could wish to approach by stealth at dead of night.

“What’s this place?” I whispered as Raffles made fast to a post.

“An unoccupied house, Bunny.”

“Do you mean to occupy it?”

“I mean our passenger to do so—if we can land him alive or dead!”

“Hush, Raffles!”

“It’s a case of heels first8, this time—”

“Shut up9!”

Raffles was kneeling on the landing-stage10—luckily on a level with our rowlocks11—and reaching down into the boat.

“Give me his heels,” he muttered; “you can look after his business end. You needn’t be afraid of waking the old hound, nor yet hurting him.”

“I’m not,” I whispered, though mere words had never made my blood run colder. “You don’t understand me. Listen to that!”

And as Raffles knelt on the landing-stage, and I crouched in the boat, with something desperately like a dead man stretched between us, there was a swish and a dip outside the inlet, and a flutter of white on the river beyond.

“Another narrow squeak!” he muttered with grim levity when the sound had died away. “I wonder who it is paddling his own canoe at dead of night?”

“I’m wondering how much he saw.”

“Nothing,” said Raffles, as though there could be no two opinions on the point. “What did we see to swear to between a sweater and a pocket-handkerchief? Only something white, and we were looking out, and it’s far darker in here than out there on the main stream. But it’ll soon be getting light, and we really may be seen unless we land our big fish first.”

And without more ado he dragged the lifeless Levy ashore by the heels, while I alternately grasped the landing-stage to steady the boat, and did my best to protect the limp members and the leaden head from actual injury. All my efforts could not avert a few hard knocks, however, and these were sustained with such a horrifying insensibility of body and limb, that my worst suspicions were renewed before I crawled ashore myself, and remained kneeling over the prostrate form.

“Are you certain, Raffles?” I began, and could not finish the awful question.

“That he’s alive?” said Raffles. “Rather, Bunny, and he’ll be kicking below the belt12 again in a few more hours!”

“A few more hours, A.J.?”

“I give him four or five.”

“Then it’s concussion of the brain!”

“It’s the brain all right,” said Raffles. “But for ‘concussion’ I should say ‘coma,’ if I were you.”

“What have I done!” I murmured, shaking my head over the poor old brute.

“You?” said Raffles. “Less than you think, perhaps!”

“But the man’s never moved a muscle.”

“Oh, yes, he has, Bunny!”

“When?”

“I’ll tell you at the next stage,” said Raffles. “Up with his heels and come this way.”

And we trailed across a lawn so woefully neglected that the big body sagging between us, though it cleared the ground by several inches, swept the dew from the rank growth until we got it propped up on some steps at the base of the tower, and Raffles ran up to open the door. More steps there were within, stone steps allowing so little room for one foot and so much for the other as to suggest a spiral staircase from top to bottom of the tower. So it turned out to be; but there were landings communicating with the house, and on the first of them we laid our man and sat down to rest.

“How I love a silent, uncomplaining, stone staircase!” sighed the now quite invisible Raffles. “So of course we find one thrown away upon an empty house. Are you there, Bunny?”

“Rather! Are you quite sure nobody else is here?” I asked, for he was scarcely troubling to lower his voice.

“Only Levy, and he won’t count till all hours.”

“I’m waiting to hear how you know.”

“Have a Sullivan, first.”

“Are we as safe as all that?”

“If we’re careful to make an ash-tray of our own pockets,” said Raffles, and I heard him tapping his cigarette in the dark. I refused to run any risks. Next moment his match revealed him sitting at the bottom of one flight, and me at the top of the flight below; either spiral was lost in shadow; and all I saw besides was a cloud of smoke from the blood-stained lips of Raffles, more clouds of cobwebs, and Levy’s boots lying over on their uppers, almost in my lap. Raffles called my attention to them before he blew out his match.

“He hasn’t turned his toes up13 yet, you see! It’s a hog’s sleep, but not by any means his last.”

“Did you mean just now that he woke up while I was in the boathouse?”

“Almost as soon as your back was turned, Bunny—if you call it waking up. You had knocked him out, you know, but only for a few minutes.”

“Do you mean to tell me that he was none the worse?”

“Very little, Bunny.”

My feeble heart jumped about in my body.

“Then what knocked him out again, A.J.?”

“I did.”

“In the same way?”

“No, Bunny, he asked for a drink and I gave him one.”

“A doctored drink!” I whispered with some horror; it was refreshing to feel once more horrified at some act not one’s own.

“So to speak,” said Raffles, with a gesture that I followed by the red end of his cigarette; “I certainly touched it up a bit, but I always meant to touch up his liquor if the beggar went back on his word. He did a good deal worse—for the second time of asking—and you did better than I ever knew you do before, Bunny! I simply carried on the good work. Our friend is full of a judicious blend of his own whiskey and the stuff poor Teddy had the other night. And when he does come to his senses I believe we shall find him damned sensible.”

“And if he isn’t, I suppose you’ll keep him here until he is?”

“I shall hold him up to ransom,” said Raffles, “at the top of this ruddy tower, until he pays through both nostrils for the privilege of climbing down alive.”

“You mean until he stands by his side of your bargain?” said I, only hoping that was his meaning, but not without other apprehensions which Raffles speedily confirmed.

“And the rest!” he replied, significantly. “You don’t suppose the skunk’s going to get off as lightly as if he’d played the game, do you? I’ve got one of my own to play now, Bunny, and I mean to play it for all I’m worth. I thought it would come to this!”

In fact, he had foreseen treachery from the first, and the desperate device of kidnapping the traitor proved to have been as deliberate a move as Raffles had ever planned to meet a probable contingency. He had brought down a pair of handcuffs as well as a sufficient supply of Somnol. My own deed of violence was the one entirely unforeseen effect, and Raffles vowed it had been a help. But when I inquired whether he had ever been over this empty house before, an irritable jerk of his cigarette end foretold the answer.

“My good Bunny, is this a time for rotten questions? Of course I’ve been over the whole place; didn’t I tell you I’d been spending the week-end in these parts? I got an order to view the place, and have bribed the gardener not to let anybody else see over it till I’ve made up my mind. The gardener’s cottage is on the other side of the main road, which runs flush with the front of the house; there’s a splendid garden on that side, but it takes him all his time to keep it up, so he’s given up bothering about this bit here. He only sets foot in the house to show people over; his wife comes in sometimes to open the downstairs windows; the ones upstairs are never shut. So you perceive we shall be fairly free from interruption at the top of this tower, especially when I tell you that it finishes in a room as sound-proof as old Carlyle’s crow’s-nest14 in Cheyne Row.”

It flashed across me that another great man of letters had made his local habitation if not his name in this part of the Thames Valley; and when I asked if this was that celebrity’s house15, Raffles seemed surprised that I had not recognized it as such in the dark. He said it would never let again, as the place was far too good for its position, which was now much too near London. He also told me that the idea of holding Dan Levy up to ransom had occurred to him when he found himself being followed about town by Levy’s “mamelukes16,” and saw what a traitor he had to cope with.

“And I hope you like the idea, Bunny,” he added, “because I was never caught kidnapping before, and in all London there wasn’t a bigger man to kidnap.”

“I love it,” said I (and it was true enough of the abstract idea), “but don’t you think he’s just a bit too big? Won’t the country ring with his disappearance?”

“My dear Bunny, nobody will dream he’s disappeared!” said Raffles, confidently. “I know the habits of the beast; didn’t I tell you he ran another show somewhere? Nobody seems to know where, but when he isn’t here, that’s where he’s supposed to be, and when he’s there he cuts town for days on end. I suppose you never noticed I’ve been wearing an overcoat all this time, Bunny?”

“Oh, yes, I did,” said I. “Of course it’s one of his?”

“The very one he’d have worn to-night, and his soft hat from the same peg is in one of the pockets; their absence won’t look as if he’d come out feet first, will it, Bunny? I thought his stick might be in the way, so instead of bringing it too, I stowed it away behind his books. But these things will serve a second turn when we see our way to letting him go again like a gentleman.”

The red end of the Sullivan went out sizzling between a moistened thumb and finger, and no doubt Raffles put it carefully in his pocket as he rose to resume the ascent. It was still perfectly dark on the tower stairs; but by the time we reached the sanctum at the top we could see each other’s outlines against certain ovals of wild grey sky and dying stars. For there was a window more like a porthole in three of the four walls; in the fourth wall was a cavity like a ship’s bunk, into which we lifted our still unconscious prisoner as gently as we might. Nor was that the last that was done for him, now that some slight amends were possible. From an invisible locker Raffles produced bundles of thin, coarse stuff, one of which he placed as a pillow under the sleeper’s head, while the other was shaken out into a covering for his body.

“And you asked me if I’d ever been over the place!” said Raffles, putting a third bundle in my hands. “Why, I slept up here last night, just to see if it was all as quiet as it looked; these were my bed-clothes, and I want you to follow my example.”

“I go to sleep?” I cried. “I couldn’t and wouldn’t for a thousand pounds, Raffles!”

“Oh, yes, you could!” said Raffles, and as he spoke there was a horrible explosion in the tower. Upon my word, I thought one of us was shot, until there came the smaller sounds of froth pattering on the floor and liquor bubbling from a bottle.

“Champagne!” I exclaimed, when he had handed me the metal cap of a flask, and I had taken a sip. “Did you hide that up here as well?”

“I hid nothing up here except myself,” returned Raffles, laughing. “This is one of a couple of pints from the cellarette17 in Levy’s billiard den; take your will of it, Bunny, and perhaps the old man may have the other when he’s a good boy. I fancy we shall find it a stronger card than it looks. Meanwhile let sleeping dogs lie and lying dogs sleep! And you’d be far more use to me later, Bunny, if only you’d try to do the same.”

I was beginning to feel that I might try, for Raffles was filling up the metal cup every minute, and also plying me with sandwiches from Levy’s table, brought hence (with the champagne) in Levy’s overcoat pocket. It was still pleasing to reflect that they had been originally intended for the rival bravos18 of Gray’s Inn. But another idea that did occur to me, I dismissed at the time, and so justly that I would disabuse any other suspicious mind of it without delay. Dear old Raffles was scarcely more skilful and audacious as amateur cracksman than as amateur anaesthetist, nor was he ever averse from the practice of his uncanny genius at either game. But, sleepy as I soon found myself at the close of our very long night’s work, I had no subsequent reason to suppose that Raffles had given me drop or morsel of anything but sandwiches and champagne.

So I rolled myself up on the locker, just as things were beginning to take visible shape even without the tower windows behind them, and I was almost dropping off to sleep when a sudden anxiety smote my mind.

“What about the boat?” I asked.

There was no answer.

“Raffles!” I cried. “What are you going to do about the beggar’s boat?”

“You go to sleep,” came the sharp reply, “and leave the boat to me.”

And I fancied from his voice that Raffles also had lain him down, but on the floor.